The classics are the classics for a reason. To rewrite them runs the risk of producing something that pales or fails in comparison. And, yet, the best retellings of the classics are like fanfic, less a copy of the original than a way of both honoring the original work and creating something new.

Plenty of literary works retell the classics—after all, the classics form part of our cultural inheritance, for better or worse, and their familiar stories offer fruitful avenues for imaginative wanderings. Some books that retell the classics stick to the same parameters as their source material, with instantly recognizable characters and settings. Others shift time periods, points of view, elements of the plot and even genres, or take minor characters from the wings and place them center stage.

SEE ALSO: 10 Must-Read Fantasy Novels for AANHPI Heritage Month

Strong retellings can stand on their own, but our top ten picks for the best retellings of the classics do more, transcending their source material to become worthy works of art in their own right.

The Chosen and the Beautiful by Nghi Vo

In The Chosen and the Beautiful, Nghi Vo retells The Great Gatsby from the point of view of Jordan Baker. While Fitzgerald’s Baker is fairly flat, Vo’s version is a queer adoptee from Vietnam. Her beauty and charm dazzle the wealthy 1920s American society in which she moves, playing golf and casting spells. Magic and ghosts abound, lending an otherworldliness to the original tale of excess and lost love. “Redo all the classics,” wrote author P. Djèlí Clark, on Instagram. “And do them like this!”

CIRCE by Madeline Miller

To hear Homer tell it, Circe was an isolated witch with a love of hedonism. When Odysseus washes ashore, she converts most of his crew into pigs, then uses magic to lure the sailor into bed. In the hands of Madeline Miller, however, Circe is herself transformed—into a complex, feminist hero who stands up to immortals and mortals alike. Before she became a bestselling author, Miller earned classics degrees from Brown and taught Greek and other subjects to high schoolers. Her knowledge of antiquity bursts from the page.

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

Born to a teenage single mom in southern Appalachia, Demon Copperhead narrates the highs (young love, athletic feats) and lows (child labor, foster care, addiction) of his attempts to be the architect of his life. Like David Copperfield, on whom he’s based, Demon is alternately angry, exuberant, anxious, patient and vengeful. Kingsolver won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for this almost universally acclaimed novel. She credits Charles Dickens for showing her how to convey the ravages of the opioid epidemic and entrenched institutionalized poverty in rural America with immediacy and sensitivity.

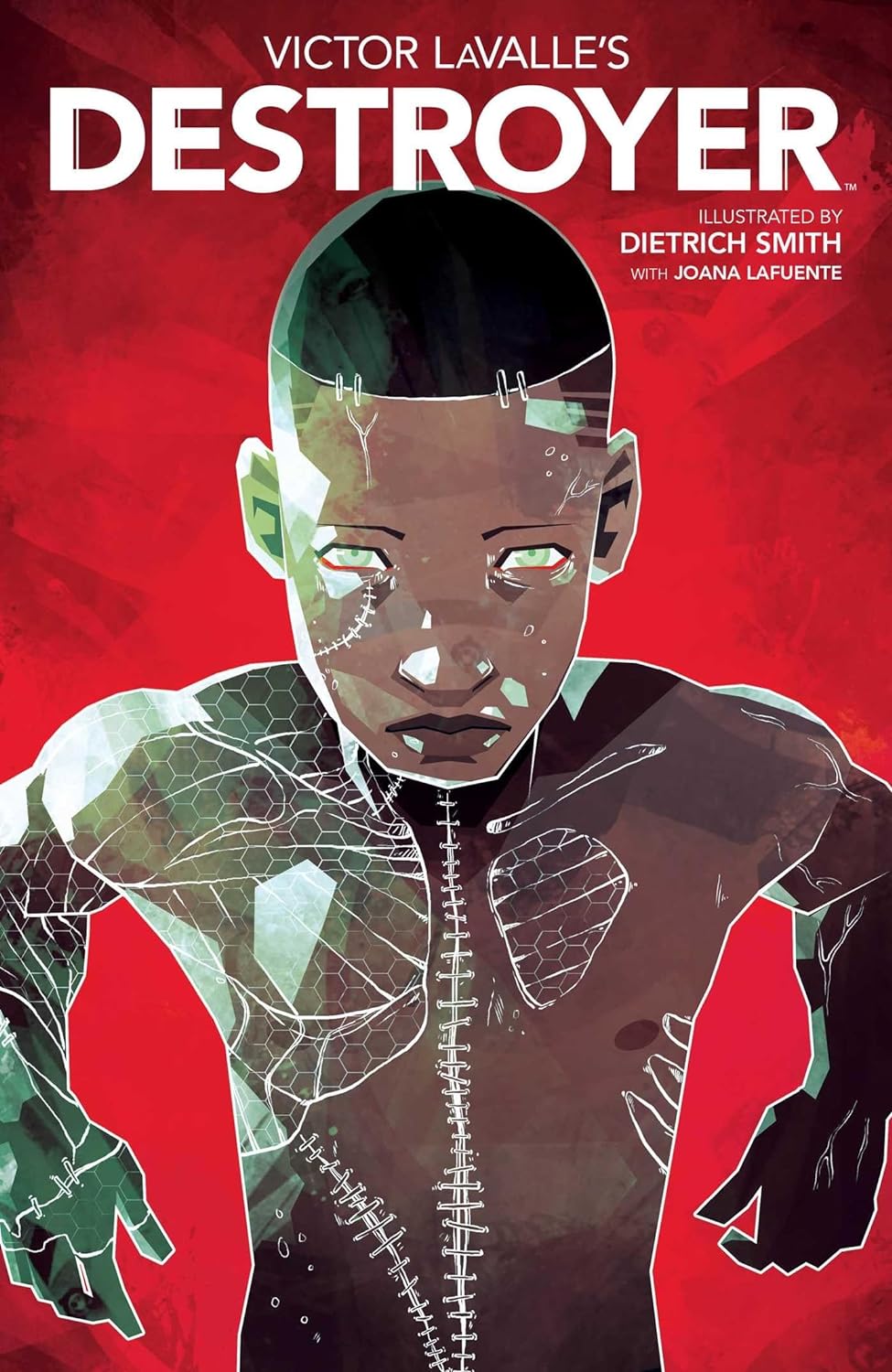

Destroyer by Victor LaValle

Within the first few pages, a skeletal creature punches a person’s heart through their back, putting the “graphic” in “graphic novel.” Created, and abhorred, by Victor Frankenstein, he’s turned into the Destroyer over the past 200+ years. As envisioned by Victor LaValle, the creature channels his anger into hurting whale hunters, industrial farmers, vigilantes and other evildoers. Soon he senses another enemy: the brilliant scientist who has resurrected her twelve-year-old son, a victim of a grisly police shooting. She also just happens to be descended from Frankenstein.

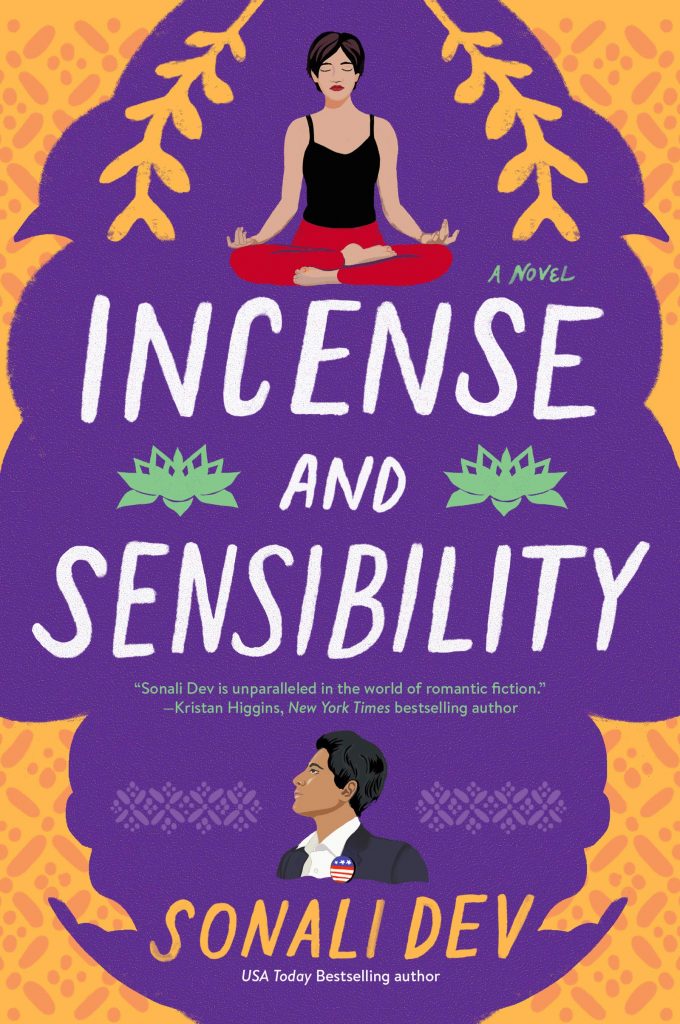

Incense and Sensibility by Sonali Dev

In 2019, Sonali Dev published Pride, Prejudice, and Other Flavors, the first book in her series of Jane Austen-inspired romances. Since then, she’s published three more titles, each focusing on the Rajes, an Indian family descended from royalty and now living in Northern California. Incense and Sensibility features a tightly wound gubernatorial candidate, Yash Raje, whose panic attacks threaten to derail his political career. Enter India Dashwood, a stress management coach who hooked up with Yash a decade ago. Will sparks ignite between the former flames?

James by Percival Everett

James retells The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the point of view of the enslaved Jim. Percival Everett reread Twain’s classic fifteen times in a row, then put it aside and let a new vision emerge. A fundamental feature of the novel is James’s linguistic gymnastics. This ability to switch from the elevated discourse he speaks with his family and other individuals of color to the dialect expected by the white people he encounters is key to his survival. Everett has written a propulsive page-turner about language and literature.

Jane Steele by Lyndsay Faye

There are a lot of ways to update the classics, but converting a meek Victorian orphan into a serial killer has to be among the most creative. “Reader, I murdered him,” announces Jane Steele, early in the novel that bears her name. Lyndsay Faye harnesses the rage women feel, both on and off the page, at being at the mercy of the patriarchy. The resulting work of satirical historical fiction not only channels Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre but also Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby and Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Wicked fun.

Macbeth by Jo Nesbø

The Hogarth Shakespeare series gives contemporary novelists the opportunity to modernize Shakespeare across genres. Handing Macbeth to Jo Nesbø was an inspired choice, allowing the master of Norwegian noir to revel in a dank atmosphere of corruption, paranoia and murderous ambition in 1970s-era Scotland. In Macbeth, the eponymous protagonist is a police inspector and former drug addict struggling with hallucinations. He’s manipulated by his lover, referred to as Lady. His city, besieged by gang warfare and a drug named “brew,” has become a hellscape. Spoiler: things go badly.

March by Geraldine Brooks

For fans of Little Women, March answers a fundamental question: what was Mr. March up to while his wife and daughters were struggling and striving in Concord, Massachusetts? Geraldine Brooks’s novel follows Mr. March, a chaplain and abolitionist. He joins the Union side of the Civil War, where he suffers from illness and witnesses horrific violence and injustice. To add richness and detail to her Pulitzer Prize-winning fictional portrait, Brooks relied on the journals of Bronson Alcott, transcendentalist, advocate for women’s rights, educator and father of Louisa May.

The Mere Wife by Maria Dahvana Headley

“Bro!” So begins Maria Dahvana Headley’s spirited translation of Beowulf. A similar irreverence infuses The Mere Wife, Headley’s retelling of the epic poem as a furious satire of suburbia. After escaping from a mental hospital, a former soldier hides in the hills, where she gives birth to a son named Gren. In time, Gren befriends a rich boy who lives in nearby Herot Hall, a gated community. Issues of class, sexuality and motherhood are all explored. But what’s truly at stake are the many ways in which monsters get made and portrayed.